Uncle Tom's Cabin

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Literary fiction

Audiobook Available

Listen to Tor, a Street Boy of Jerusalem in the app. It's free and ad-free.

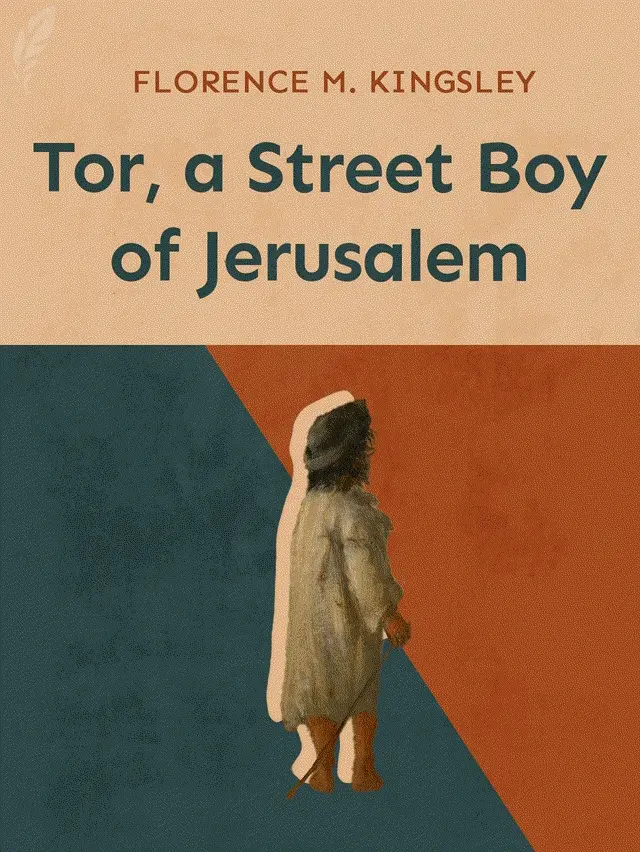

In the bustling streets of Jerusalem, a spirited street boy named Tor discovers the power of friendship and faith, navigating a world of challenges and hope. Will he find his place and a sense of belonging in this ancient city?

Audiobook Available

Listen to Tor, a Street Boy of Jerusalem in the app. It's free and ad-free.

In the bustling streets of Jerusalem, a spirited street boy named Tor discovers the power of friendship and faith, navigating a world of challenges and hope. Will he find his place and a sense of belonging in this ancient city?

Total ratings

3

Average rating

4.3

/ 5

★★★★★

Rating breakdown

Last 12 months

Total reviews

No reviews yet.